India's biggest cover-up Read online

Table of Contents

Prologue

1. Bose mystery begins

2. Big brother watching

3. Enter the Shaulmari sadhu

4. Shooting star Samar Guha

5. A proper inquiry at last

6. The search for Bose files

7. Ashes which turned to bones

8. How India dealt with Russia over Subhas Bose’s fate

9. The ‘Dead Man’ returns

10. Why ‘Dead Man’ tale can’t be wished away

11. Subhas Bose alive at 115?

12. Resolving the mystery

Appendix I: The loot of the INA treasure

II: The strange case of Taipei air crash

III: Views of Subhas Bose’s family on his fate

IV: Was Subhas Bose a war criminal?

V. The land of conspiracy theories

VI. The men who kept the secrets

About the author

Notes on public domain information, including declassified records and information accessed under transparency laws

COPYRIGHT

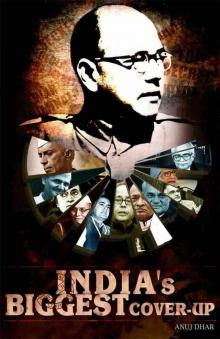

India’s biggest cover-up. Copyright © 2012 by Anuj Dhar. Cover art by Koushik Banerjee. www.subhaschandrabose.org/ibc.php

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission, except for brief quotations in articles and reviews.

The book has been priced low to discourage piracy. Please respect the author's lifetime of work and get your copy from Amazon only.

The following stamps appear on the images to indicate source of the documents and pictures.

NAI: The National Archives of India, New Delhi.

RTI: Document obtained under the Right to Information.

NMML: The Nehru Memorial Museam and Library, New Delhi.

TNA: The National Archives, Kew.

NARA: The National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

CIA: Document obtained from the CIA under the Freedom of Information.

AP: Associated Press (AP Photo)

NAA: The National Archive of Australia, Melbourne Office.

DB: Deutsches Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive)

ABF: Amiya Nath Bose family.

JP: Jayasree publications, Kolkata.

PI: Still classified/out of public domain records obtained in public interest.

CONTENTS

Prologue

1. Bose mystery begins

2. Big brother watching

3. Enter the Shaulmari sadhu

4. Shooting star Samar Guha

5. A proper inquiry at last

6. The search for Bose files

7. Ashes which turned to bones

8. How India dealt with Russia over Subhas Bose’s fate

9. The ‘Dead Man’ returns

10. Why ‘Dead Man’ tale can’t be wished away

11. Subhas Bose alive at 115?

12. Resolving the mystery

Appendix I: The loot of the INA treasure

II: The strange case of Taipei air crash

III: Views of Subhas Bose’s family on his fate

IV: Was Subhas Bose a war criminal?

V. The land of conspiracy theories

VI. The men who kept the secrets

About the author

Notes on public domain information, including declassified records and information accessed under transparency laws

Prologue

Information Commissioner AN Tiwari’s darting eyes seized the three 30-something men sitting across the table. Only Sayantan Dasgupta was conspicuous by his tall, dark, handsome presence. The other two were short, plump and sported unfashionable short hair. Chandrachur Ghose would have looked studious in his chubby countenance and glasses but for an occasional meaningless smirk. The third harried-looking person was me. Tiwari’s anxious eyebrows were now wrinkling his forehead.

“Haven’t you people anything better to do?” he asked.

The room we were sitting in was in a spruced up part of an otherwise worn-out building temporarily housing offices of the Central Information Commission, the watchdog body created only two years earlier to regulate India’s new freedom of information regime. The Right to Information Act, 2005, had elevated the country into a select group of nations giving their public the right to seek information from their government. Of course, to respond or not was the Government’s prerogative within the ambit of the Act. In our case the Government hadn’t to our satisfaction, and so there we were.

There was a muted laugh, and Tiwari frowned to silence the two middle-aged, middle-level Ministry of Home Affairs officials to my left.

“Sir, this is...”

The commissioner was not keen to hear counter-arguments from us nevertheless.

“Look, I was born in Cuttack. I went to the same school as Netaji did. I can do without your perspective on the mystery.”

Tiwari needed no lessons in history or anything from us. But it was not just the history we were sitting there for.

We learn about the past largely from the historians and researchers working on the information available in public domain—in archives, libraries or in private collections. There isn’t much the historians can do except to speculate when they know something is there but can’t reach it. The liberty of speculation is lost when they don’t even know that something exists.

Ours was essentially a case of history being held hostage to state secrecy. And we were lucky to be making our case before a man who had been a bureaucrat all his life before being appointed on the information panel.

As in the preceding decades, in 2006, when we made our case before the Central Information Commission, a standard lookback at Subhas Chandra Bose climaxed with the breaking point in his relations with the Congress party in 1939. The twice-elected Congress president’s run-in with Mahatma Gandhi was the turning point of the Indian freedom struggle. Bose stood for treating non-violence and satyagraha as only a means to an end—“to be adjusted and altered, as exigencies and expediency demand”—on the path to swaraj, or complete freedom from the colonial rule. Saint Gandhi, on the other side, would “adhere to that ideal of highest standard of non-violence, even if the pursuit means sacrificing and giving up the political goal of swaraj”. [1]

Gandhi and Bose had not hit it off well from the first time they faced each other in Mumbai’s Mani Bhawan in 1921. The latter had just returned from London having quit the ICS, the best job any youngster could land in those days. For a man who had no experience of public life and was 28 years junior to the biggest phenomenon of Indian politics, Bose had the gumption to tell Gandhi that his plan to make India free was fudgy. Gandhi had the greatness to counsel Bose to get clarity from Chitta Ranjan Das.

Over the next two decades or so, most of which was spent in either jails or exile in Europe, Bose differed on several issues with the man he would call the Father of the Nation. He wore his heart on his sleeves throughout over a range of issues—the execution of revolutionary Bhagat Singh, possible dominion status for India, the need for modern industry, intra-party democracy and so on.

With that sort of backdrop, Congress president Bose wasn’t going too far. In his own words, “the Gandhi Wing would not follow” his lead and he “would not agree to be a puppet president”. [2] Not allowed to work on his own terms, Bose was hounded till he stepped down. He created the Forward Bloc within the party, which further annoyed the entire top-rung leadership. They snatched the charge of Bengal state Congress from him and debarred him from contesting for any position in the party for three years. Screaming headlines in newspapers at that time would have you believe it was Bose, not the British, the top leadership was probably at war with.

The bitter smile that Dilip Kumar Roy saw on his

best friend’s face was the result of the “most unkindest cut of all”. “Subhas Bose punished for ‘grave act of indiscipline’,” an 8-column Hindustan Times headline read. To Roy, “it was not the discipline that he minded. But that he was asked to eat humble pie and beg the high command to forgive him, when the boot was on the other leg”. [3] Roy felt that his friend was put through “the unjust humiliation” only because he had “the courage of his conviction and said openly that he did not believe in the cult of non-violence”. [4]

Many of the stalwarts who backed Gandhi against Bose at that time weren’t the peaceniks they professed to be. When they and their followers were running India years later, brute state force and streaming inputs from the Intelligence Bureau and not hallowed Gandhian principles saw India through. Goa was not liberated through satyagraha. Rebellious Mizos weren’t sent emissaries from Gandhidham; they got poundings from the Indian Air Force fighter planes.

In 1940 Bose was a nowhere man. “Those who do not go with Gandhiji are politically dead,” [5] said a Gandhi supporter about the 43-year-old, just not ready for that sort of fate. So he exfiltrated himself to another theatre from where he could fight freely. It was in the national interest, but too bad it turned out to be in Nazi Germany. It could have been Russia, but the Soviets were just sympathetic. Nothing more. For all the right things it stood for, the United States sided with British colonialism. Bose came to despise the US. He wanted his country to be free above anything else. So, unmindful of dangers to his life, he escaped from British custody in India, crossed into Afghanistan and—passing through the lawless land which is now the haunt of Taliban and Al-Qaida—found his way to Berlin via Moscow and Rome. No Indian leader of his stature could ever think of the things he did.

India’s star freedom fighter was born in Nazi Germany. In a remarkable image makeover for Bose, from the politician Subhas babu, he became the military leader Netaji. As Netaji, Bose’s two initial contributions to the idea of modern India were a national slogan and a national anthem. His political opponents at home were compelled to accept them years later. They couldn’t think of anything comparable.

On the run from the biggest power on earth, Bose mixed fearlessly with the deadliest men of his times. They were his friends by default, for they were the enemies of his enemy. Apply the body language rules to the pictures which have recently been made public through Wikimedia Commons by the German Federal Archive and you will see Bose on the high table with Hitler's top brass, having them eating out of his hand.

The tilt in monster Heinrich Himmler’s mannerism is for real. Obviously, like Benito Mussolini before him, the Reichsführer was drawn to the fugitive Indian like an iron clip to a magnet. The admiring look in Adolf Hitler’s devilish eyes as Bose gives him a firm handshake is an iconic freezframe for many, continuing embarrassment for others and a stick to beat Bose with for those who abhorred him for entirely domestic reasons.

A German pointed out to me that before he joined the Axis, Bose had opposed Gandhi’s protégé Jawaharlal Nehru’s idea that the European Jews could be given sanctuary in India. I submitted that most Indians of that time couldn’t think of anything else except their own emancipation. On a personal level, Bose was as much humane and enlightened as any other Cambridge alumni. Between 1933 and 1939, for example, he had for friends Kitty and Alex, a sensitive, newly married Jewish couple in Berlin. Before they met, Kitty had heard an American priest in Berlin calling Bose a “traitor to the British government”. But in their first meeting, Bose came across to her as a “mystic, a spiritual man”. In their last, he told her to “leave this country soon”. [6]

The couple went to the US and from her Massachusetts home in 1965 Kitty Kurti wrote her tribute for “Netaji”. She reminisced about the various issues they had discussed. Bose had told her about certain Hindu holy men who while physically far away could still be able to “appear and talk to you”. [7] Kitty noted that Bose “did not attempt to hide” [8] from her his deep contempt for the Nazis. In the same vein, he cited India’s exploitation by British imperialism and explained why he had to do business with the Nazis. “It is dreadful but it must be done. …India must gain her independence, cost what it may,” [9] he told the couple after a meeting with Hermann Göring. Of Jews, Bose said, “they are an old and fine race” gifted with “depth and insight” and felt that they had been “miserably persecuted” across the centuries. [10]

It was India’s interest that mattered to Bose foremost. Nehru’s idea about bringing European Jews to poverty-stricken India was airy, unworkable and only good for grabbing headlines. So long as Nehru and his family ruled India, I told the German, Israel was not allowed to open its embassy in New Delhi. There is an old Indian saying: An elephant has two sets of teeth. One for the purpose of eating and the other for flaunting.

Bose’s violent push for India’s freedom during the Second World War with his quickly assembled, Japan-backed Indian National Army (INA) had a great start, or so it seemed. Bose’s deep baritone on the radio sent Indian hopes soaring unbelievably high. And yet the dreams of a blitzkrieg by Bose’s non-existent airplanes never materilised. His exhortation “George Washington had an army when he won freedom. Garibaldi had an army when he liberated Italy” [11] came to nothing when the action began. The INA men were routed in battlefield, at the very hands of the Indian mercenaries enrolled in the British Indian Army.

An Indian Army assessment of 1946 said “the INA was 95% ‘ballyhoo’ and 5% ‘serious business’”. It was “still an embryo organisation” when it went to war; a “purely guerilla force…with no aircraft, no artillery, no heavy mortars, no tanks or AFVs,” a “David against Goliath but a David without a sling”. Out of 15,000-odd INA soldiers who actually saw action, 750 were killed; 1,500 died of disease; 2,000 escaped; 3,000 surrendered and the rest 7,000 fell into the British hands. “It was never a cause of real trouble or annoyance to the Allies,” [12] the report concluded.

The trouble was just starting. An Indian Army officer intermingled with the imprisoned INA men “awaiting repatriation to India” to get a sense of their outlook. He reported back that it was no use trying to belittle Bose: “He is regarded by them as a ‘Leader’ who is honest, utterly sincere and who has raised the status of the Indian community in the Far East far above that of the other minorities under Japanese occupation.” [13] These people were then brought to India and put on trial at the very place they had vowed to march into. But the idea to make the Red Fort trials the Indian version of Nuremberg and Tokyo trials backfired. Bose’s war was justified.

The humiliation of the INA soldiers—Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian—galvanised the Indians like they hadn’t been ever since India was brought under direct British government rule. The Governor of the present-day Indian state Uttar Pradesh wrote to the Viceroy in New Delhi in November 1945 that those hitting the streets were actually suggesting that “Bose is rapidly usurping the place held by Gandhi in popular esteem”. [14] INA’s GS Dhillon openly engaged in fistfights with his captors and dared the jury, including future Indian Army chief KS Cariappa, to hang him. They would have done so without any delay, but in the dead of night, city walls were plastered with handbills warning of bloody retribution. In 1946, the Intelligence Bureau—the spy agency that had monitored the Indians since 1885—reckoned that “there has seldom been a matter which has attracted so much Indian public interest and, it is safe to say, sympathy”. [15] The British were wise enough to see the writing on the wall.

“But where was Netaji then?” I wondered as a school boy. Then, there in one corner of a history book approved by the Government, I read that he had died in an air crash in Taiwan. In college years I learnt that there was some dispute about the crash just after the end of the war, Bose’s cremation in Taiwan and his assumed ashes kept in a Japanese Buddhist temple. Now I surf the net and see a BBC story saying that his “body was never recovered, fuelling rumour and speculation...that Bose survived the crash”. [16]

I wonder wh

y do we Indians continue to think about Bose's fate? We are the sort of people who have never let any tragedy of howsoever gargantuan proportions overwhelm us. Millions died when Partition occurred and not a stone stands in their remembrance anywhere on Indian soil. I don’t know if it is a good or bad thing, but we have a knack for putting the past behind us. Controversies surround the death and assassinations of our three prime ministers and yet the cumulative interest in them is not a patch on the Bose mystery. So, there has got to be a little more than rumours and speculations for the people to keep it alive so many decades after Bose’s political clout dissipated even from his home state Bengal.

In 1956 and again in 1970, the governments of Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi were pressurised into launching probes to resolve the issue. The inquiries of INA veteran Shah Nawaz Khan and well-known judge GD Khosla backed the air crash theory and yet there was no end to what some people believed. They claimed that the official inquests were fixed.

In the 1960s an unbelievable urban tale had conjured up Bose as a fugitive holy man in a remote corner of India. Kitty Kurti wondered if her friend was a “sanyasin, appearing now and then in this or that village”. [17] Those claiming to be speaking for “Bose” raised the bogey of a war criminal tag he couldn’t shake off due to the complicity of the Indian government, which had inherited all the international obligations of the Raj. Some others blamed the Nehru government for planting the holy man tales “knowing well” that Bose had died not in Taipei, but subsequently in a Siberian gulag.

India's biggest cover-up

India's biggest cover-up